There was in him a vital scorn of all:

As if the worst had fall’n which could befall,

He stood a stranger in this breathing world,

An erring spirit from another hurled …

So much he soar’d beyond, or sunk beneath

The men with whom he felt condemn’d to breathe.

These lines, from Lord Byron’s tragic poem “Lara” (1814), vividly convey the mood of the tormented Romantic genius. He stands alone on a frozen cliff, contemptuous of all he sees below: the bourgeois society with its provincial normality, the masses caught up in a daily struggle for a slightly larger slice of the pie, the whole civilized world with its games, its rules, its falsehoods. He, the genius, is alien to all that. He fell from a different world, yet is condemned to breathe the same air as the plebeians.

Lord Byron did not think it worthy of him to breathe city air. He was destined for radically different heights. After voluntary exile from England, wanderings across Europe and a few years of living in Italy, he decided, at the age of 35, to join the struggle of nascent Greek nationalism against the Ottoman Empire. After equipping the Greek fleet at his own expense, and despite his complete lack of military experience, he placed himself at the head of a force that was preparing to capture the fortress of Lepanto, at the mouth of the Gulf of Corinth. Only the fact that he fell ill and died from complications of influenza prevented him from suffering a heroic death on the battlefield.

Lord Byron did not think it worthy of him to breathe city air. He was destined for radically different heights. After voluntary exile from England, wanderings across Europe and a few years of living in Italy, he decided, at the age of 35, to join the struggle of nascent Greek nationalism against the Ottoman Empire. After equipping the Greek fleet at his own expense, and despite his complete lack of military experience, he placed himself at the head of a force that was preparing to capture the fortress of Lepanto, at the mouth of the Gulf of Corinth. Only the fact that he fell ill and died from complications of influenza prevented him from suffering a heroic death on the battlefield.

Byron was exceptional simply because of his talent and his fortune. Around him, young people sought a life of daring and adventure, of gushing emotions and soul-searching. Interestingly, in the view of those Romantics, such a life was obliged to interweave rebellion and truth, as though truth that does not rebel is not valid, and rebellion that does not involve a quest for truth is not true rebellion. Byron thus embodied a general European phenomenon.

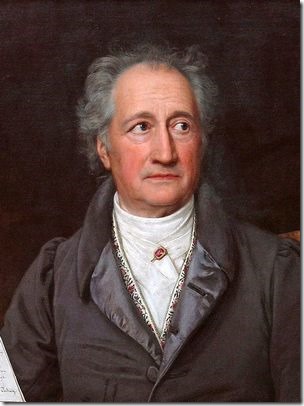

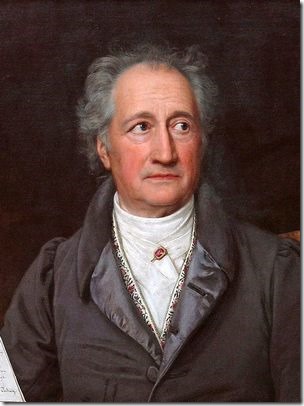

Exactly 40 years before “Lara” appeared, Goethe published “The Sorrows of Young Werther.” Goethe was only 24 when he wrote the epistolary novel that made him the voice of his generation. Werther, the tormented artist, describes in letters to his friend Wilhelm his impossible love for Charlotte, who is engaged to a different man. Ultimately, his intense, terrible love leads Werther to commit suicide, but not before he shares with his friend some insights. Young Werther finds in nature the balm for his soul, which seeks to truly live and create.

According to Werther, we must

keep to Nature alone in future. Only nature has inexhaustible riches, and only Nature creates a great artist. A good deal can be said of the advantage of rules and regulations, much the same as can be said in praise of bourgeois society. A man shaped by the rules will never produce anything tasteless or bad, just as a citizen who observes laws and decorum will never be an unbearable neighbor or an out-and-out villain; and yet on the other hand, say what you please, the rules will destroy the true feeling of Nature and its true expression! (translation by Michael Hulse).

The world of laws and rules, the world of settled folk, is perfectly reasonable and safeguards us from evil. However, its reasonableness is also its weakness. It’s average, ordinary, logical. It is incapable of soaring. And, as such, it destroys in people any real contact with nature – which is to say that it destroys the place of truth within us. It subdues our creativity and thrusts us onto a fixed, preordained track. The only course, then, is to rebel against it.

Close game with truth – and death

Everyone who listens to the voices emanating from the circles of “hilltop youth” in the West Bank will discern salient resemblances to the sentiments expressed in the quotations above. The soul-searching, the desire to get close to nature, the contempt for the society they have abandoned, the rebellion that is construed as truth and the close game with death. There’s nothing new in this and we didn’t need the murder of the Dawabsheh family in the village of Duma last July to hear it.

Everyone who listens to the voices emanating from the circles of “hilltop youth” in the West Bank will discern salient resemblances to the sentiments expressed in the quotations above. The soul-searching, the desire to get close to nature, the contempt for the society they have abandoned, the rebellion that is construed as truth and the close game with death. There’s nothing new in this and we didn’t need the murder of the Dawabsheh family in the village of Duma last July to hear it.

In an article on radical settler youth in the hills of Samaria, published in the August 2007 issue of the now-defunct settler magazine Nekuda, Shoshi Greenfield quoted Uri Alon, who worked with young people at risk, who observed that, “youth who are looking for truth without compromises, and not the compromising, tepid truth of the adults’ world.”

In early January, the religious-Zionist newspaper Makor Rishon published an anonymous testimony by someone who was active in the hilltop youth 15 years ago. “I grew up in the groves of the religious-Zionist movement, but I was scornful of it and of its key figures,” he wrote.

They seemed to me old-fashioned, with a Hanan Porat-type of naivete [a reference to the late right-wing rabbi and political leader], disconnected from the new way of life that included working the land and tending sheep, a deep connection to the earth, making do with little and displaying esprit de corps … The Haredi [ultra-Orthodox] model of an uncompromising disconnect and of creating a sealed-off autonomy amid the Israeli licentiousness fit us like a glove.

This is not a new phenomenon, and its characteristics are largely fixed: a rebellion against parents and society, a quest for truth, an unwillingness to compromise. Last December, journalist Karni Eldad published an interview in the newspaper Maariv with Eliashuv Har Shalom, 26, the resident of a remote settlement outpost. He explained,

There [were] always those who sacrificed themselves on the altar of truth, ready to pay the price, and these fellows are ready to pay the price. But the question is: Where does this place us as a society? We are not ‘wild weeds,’ we are fruit-giving trees. You raised us. Suddenly you are dissociating yourselves from us? Suddenly we are not part of you?… What is Zionism? We don’t know what ‘Zionism’ means anymore. I understand the people who distance themselves from the term, because now it’s like being ‘next to’ or ‘just like’ the real thing. I know what Zionism used to be – draining swamps and Beit Hadassah in Hebron. But if being a Zionist is to apologize for your very existence, then there’s a question whether I am a Zionist. Today we are spitting in the face of Zionism. True Zionists would not have turned ‘nationality’ into asterisks on the ID card.

Let’s look again at the elements that recur in these last few quotations: contempt for society; rejection of compromise and interpretation of it as being disingenuous; search for truth by means of breaking away from the commonalty; closeness to nature as an ideal; and the self-perception of being authentic successors to the religious-Zionist movement and of the Zionist movement as such. Thus the roots of hilltop youth lie in European Romantic streams, and the ethos their movement expresses is merely a Jewish translation of the Romantic quest for authenticity.

From Romanticiam to Religious Zionism

Still, we need to see what sets hilltop youth apart from classic religious Zionism – which also owed a large debt to Romanticism. The Romantic movement, emerging at the end of the 18th century, was never an orderly, sharply defined phenomenon, accommodated a broad range of artists and thinkers, ideas and creative works. At the same time, it can be said simplistically that, as a reaction to the Enlightenment, which prioritized reason and viewed it as the eternal, universal and dominant element in man, Romanticism sought to elevate emotion, creativity and uniqueness to the highest rung, viewing these as essences to be investigated in the course of the journey undertaken by the individual – or the nation – to self-fulfillment.

Alongside writers like Byron and Goethe, who manifested in their lives and their works a personal, sentimental search for self, there were others who believed that the basic element of that search lay not in the individual but in the national collectivity. Such late-18th-century thinkers as Johann Gottfried Herder and Johann Gottlieb Fichte saw the individual as a derivative of the culture and the nation in which he originated. Only if the individual recognized his essence as a cell within the national organism could he realize himself fully, they held. Life was unity before it was multiplicity, an interconnecting flow and not static alienation. The individual is bound by every fiber to the whole, and even if he wishes to, he cannot disconnect and live his life alone. A full life is expressed in the individual’s faithfulness to – if not in his actual merging with – the collective.

Rabbi Avraham Yitzhak Hacohen Kook (1865-1935) was very much influenced by Romantic thought. For him, too, reality is a tremendous spiritual unity, and for him, too, the individual’s quest for selfhood is equivalent to his quest for the truth – and both are manifested in the Torah and the God of Israel. In his writings, Kook fuses the individual track (self-fulfillment by merging with the totality of things) and the national track (self-fulfillment by merging with the nation).

Rabbi Avraham Yitzhak Hacohen Kook (1865-1935) was very much influenced by Romantic thought. For him, too, reality is a tremendous spiritual unity, and for him, too, the individual’s quest for selfhood is equivalent to his quest for the truth – and both are manifested in the Torah and the God of Israel. In his writings, Kook fuses the individual track (self-fulfillment by merging with the totality of things) and the national track (self-fulfillment by merging with the nation).

However, it is the latter that has been emphasized by the rabbi’s pupils and disciples, particularly in the doctrine of his only son, Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook (1891-1982). Comprehensive research has shown how the stance that sanctifies nationhood was magnified in the writings of Rabbi Zvi Yehuda, at the expense of his father’s more personal and individual-directed writings.

The religious-Zionist movement – which beginning in the 1970s adopted the concepts presented by the senior Rabbi Kook as a central meta-narrative – has expressed the broader, national orientation in its approach (which attributes supreme importance, even holiness, to the state’s institutions), by adopting the ethos of self-sacrifice and of acting for the general good, and in perceiving itself as the authentic successor to the Zionist movement. All these notions, of course, placed the emphasis on the collectivity at the expense of the individual.

Since the latter half of the 1980s, the religious-Zionist movement has also seen the rise of the phenomenon of the personal, spiritual search that seeks to give expression to creativity, uniqueness and an intimate relationship, essentially private, with the Divinity. For their textual and conceptual platform, those in the forefront of this approach – at the time, Rabbis Shagar (Shimon Gershon Rosenberg) and Menachem Froman, and afterward also Ami Olami, Benny Kalmanzon and Dov Singer – drew on Hasidic materials, hence the term “neo-Hasidism” that is applied in general to a phenomenon that has since spread greatly and resisted attempts to suppress it. Today, the idea of embarking on a personal spiritual quest is very widespread in the religious-Zionist public.

The Ethics of Authenticity

The hilltop youth, including the terrorists they have spawned, embody a private case of this general phenomenon. Here, self-fulfillment within the religious-Zionist movement is no longer perceived to be conditional on one’s connection to the national collective; on the contrary, it is based on a personal quest for self-expression. In contrast to the phenomena of neo-Hasidism as a whole, these young people do not make do with embarking on a personal spiritual journey that is parallel to life within a greater society: They are looking for authenticity precisely by unequivocally withdrawing from the generality. It is, indeed, their extreme rebellion against the society at large that allows them to consider themselves to be the only ones who are truly faithful to Torah and God.

This is not a chance development. It is how the ethos of authenticity works.: embodying a modern ideal, and typifying Romanticism. As Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor explains in his book “The Malaise of Modernity,” for an action to be considered authentic, it must inherently be exceptional. If I come to a New York law office in a suit and tie and declare that I dressed that way because I felt it was an authentic expression of myself, I will get bemused looks – because what’s authentic about a suit and tie? But if I arrive barefoot, in torn jeans, or in a top hat, my colleagues will likely interpret that as an authentic reflection of my original and unique personality.

Authenticity, according to Taylor, entails creativity, originality and a rebellion against conventional norms – that’s how it’s created. However, if this is indeed so, we have to understand that authenticity is closely bound up with those rules. Only an act that in our society is thought to be original or creative can be considered authentic. Even if it poses as a personal quest for maximum originality, in its essence, it is a dialogue with the society from which it emanated. In fact, I would argue that achieving so-called authenticity will always involve not only a rebellion against certain societal norms and values, but also radicalization of other norms and values of that same society.

This is how we must understand hilltop youth. No doubt, they are rebelling against the society around them. They are scornful of their parents, reject rabbinical authority, and of course are breaking the laws of the state. In their Romantic pursuit of authenticity, they are bound to turn their back on the society from which they came.

We need to look closely, however, at what these young people are rebelling against and what they are not rebelling against. Their rebellion does not take the form of volunteering in left-wing organizations such as Breaking the Silence or Peace Now. Nor do they stop being religiously observant, buy large motorcycles or revel in celebrations of sexual liberation. Because the greater society always defines for us even what is authentic, if we want to be considered as such by others, it is not possible for us to rebel against all its conventions. As noted, a central part of our rebellion will not lie in breaking the rules, but in radicalizing them.

We need to look closely, however, at what these young people are rebelling against and what they are not rebelling against. Their rebellion does not take the form of volunteering in left-wing organizations such as Breaking the Silence or Peace Now. Nor do they stop being religiously observant, buy large motorcycles or revel in celebrations of sexual liberation. Because the greater society always defines for us even what is authentic, if we want to be considered as such by others, it is not possible for us to rebel against all its conventions. As noted, a central part of our rebellion will not lie in breaking the rules, but in radicalizing them.

Let us return to Lord Byron. He rebelled against his milieu by leaving his homeland, England, without intending to return. He disdained bourgeois society and its conventions. However, his greatest adventure, in which he was killed, was based on a desire to cling tightly to values that were widely accepted in his time: He fought for nationality and freedom. We find a similar pattern in Goethe’s young Werther. He withdraws from society and tries to lead a simple life, close to nature. He spurns the “laws” and the “general welfare.” However, his life ends because he is so faithful to the obligatory call of love, a familiar and accepted ideal.

The rebellion of hilltop youth is against the society from which they sprang, which they consider spineless, compromising, unauthentic and untrue. Their rebellion is against the religious-Zionist rabbis for the same reasons. However, they are not rebelling against the education they received – on the contrary, they are radicalizing the values accepted in their milieu: settlement in Judea and Samaria, strict halakhic observance and an imperious attitude toward the Palestinians.

As another representative of this group, Zvi Sukkot, wrote on his Facebook page on December 21,

Whoever burned the house in Duma did not do it because he thinks he knows more about security than the defense minister, but because he thinks that the Torah understands more than the defense minister. And there is revenge in the Torah. He see himself as representing the Torah in this world. You were the ones who gave him that education. When you opposed peace with Arabs, when you built without permits and became champion manipulators in money laundering, [when] you said that under no circumstances will women sing in the IDF, when you talked about the state and the High Court of Justice in criminal terms. And you did it all in the name of the Torah!!

Hilltop youth are rebelling against the rabbis who were their teachers, but not against their religious teachings. Rather, they are using those teachings as a spring: the further they stretch them, the more intense they become. It is precisely the radicalization of these teachings, and their fundamentalist understanding of them, that create an authentic Jewish existence for these individuals.

Every society that is committed to certain common ideals, every society that is ideological, summons up extreme, sometimes violent fringes, and the religious-Zionist community is not alone in this. What needs to be examined in regard to hilltop youth is not their extremism, but the values on which they are establishing their interpretation of Jewish authenticity. The mold into which those values are cast is Romantic, but the material from which they are forged is found in the Jewish tradition, and the impression arises that sometimes not only is it not neutralized, but that its praises are sung. In such a situation only one step separates perception of it in a controlled manner that is aware of the gap between the ideal and the reality, and its zealous interpretation, which is a prelude to violence.

:

—

Published in Haaretz

In contrast, Bezalel Smotrich and Itamar Ben-Gvir (Israel’s Minister for National Security) display a fundamentalism resembling that of extreme Evangelical Christianity, in that it applies literal understanding to the Bible and aims to implement that understanding to the transformation of the political and social reality around them. This type of fundamentalism is committed to zealous authenticity in belief and practice, and maintaining a dogmatic understanding of tradition, shows very little aptitude towards pragmatism.

In contrast, Bezalel Smotrich and Itamar Ben-Gvir (Israel’s Minister for National Security) display a fundamentalism resembling that of extreme Evangelical Christianity, in that it applies literal understanding to the Bible and aims to implement that understanding to the transformation of the political and social reality around them. This type of fundamentalism is committed to zealous authenticity in belief and practice, and maintaining a dogmatic understanding of tradition, shows very little aptitude towards pragmatism. And he is not alone. Mr. Ben-Gvir is a longtime member of circles following the late Rabbi Meir Kahane’s teachings, a vile racist who whose Kach movement was designated a terrorist organization by both the US and Israel. Ben-Gvir himself was twice convicted for supporting a terrorist organization following his activities there.

And he is not alone. Mr. Ben-Gvir is a longtime member of circles following the late Rabbi Meir Kahane’s teachings, a vile racist who whose Kach movement was designated a terrorist organization by both the US and Israel. Ben-Gvir himself was twice convicted for supporting a terrorist organization following his activities there.