At a certain point in his book “The Great Cat Massacre,” American historian Robert Darnton surveys the diary of the policeman-investigator Joseph d’Hémery, who surveilled intellectuals in mid-18th century Paris in search of atheists. “D’Hémery did not separate impiety from politics. Although he had no interest in theological arguments, he believed that atheism undercut the authority of the crown.”

D’Hémery’s problem with atheism was not that it contradicted the tenets of his own belief. He found atheism dangerous because it undermined the foundations of society. Those who denied the authority of the heavenly king could just as easily deny the authority of the earthly king. Police officers, who were responsible for preserving public order, considered it their duty to root out atheism, and atheists – or at least those who were brave or foolish enough to declare themselves as such – were imprisoned, tortured and executed.

It wasn’t just a problem of over-policing. In 1793, while crushing the world order and shaping a new society on the battlefield of the French Revolution, the leader of the revolutionaries, Robespierre, declared that atheism was dangerous and “aristocratic” (the ultimate insult from his viewpoint). The constitution of the American state of Tennessee, which was signed around the same time, recognized freedom of conscience but nevertheless forbade appointment to public office of any “person who denies the being of God, or a future state of rewards and punishments.” The framers of the document were willing to accept any belief, but not the absence of any belief. Even Abraham Lincoln could declare that were it not for the Bible and the New Testament, “we could not know right from wrong.” Without belief, chaos reigns.

It wasn’t just a problem of over-policing. In 1793, while crushing the world order and shaping a new society on the battlefield of the French Revolution, the leader of the revolutionaries, Robespierre, declared that atheism was dangerous and “aristocratic” (the ultimate insult from his viewpoint). The constitution of the American state of Tennessee, which was signed around the same time, recognized freedom of conscience but nevertheless forbade appointment to public office of any “person who denies the being of God, or a future state of rewards and punishments.” The framers of the document were willing to accept any belief, but not the absence of any belief. Even Abraham Lincoln could declare that were it not for the Bible and the New Testament, “we could not know right from wrong.” Without belief, chaos reigns.

It is difficult for us today to grasp not only how rare denial of God’s existence was, but how frightening it was for our forebears several centuries ago. Atheists to them were what pedophiles are for us: not only repulsive individuals, but in a fundamental way completely unfathomable. How could anyone deny God’s existence? How could anyone reject what was self-evident, what was necessary for life as we know it to be possible? Could an upright, worthy life be lived without God? Atheists threatened not only belief but the entire framework of society. The horror they aroused did not stem from fear for the future of religion, it welled up from anxiety about the moral virtues, about the social fabric itself.

For countless generations, atheism terrified Europeans. How, then, did we arrive at a situation in which atheism is perceived as a legitimate stance, one that according to many constitutes the only realistic, rational and respectable point of view?

In attempting to explain the acceptance of atheism it would be easy to whip out the familiar argument about the scientific revolution and its revelations. It would be simple to explain that after it became known that the Earth revolves around the sun and is not itself at the center of the universe; after it was established that the world is billions of years old and not 5,000; after we discovered that the Torah is comprised of various documents and was not written by Moses; and after we understood that humankind came into being in an evolutionary process and not “on the first Friday” – that after all this, a trans-European process of “disenchantment” occurred, at the end of which was abandoned and non-belief was adopted.

According to this explanation, the Age of Enlightenment effectively marks the the completion of humanity’s maturation, its liberation from the shackles of mythology and fairy tales, and its emergence into rationality. Immanuel Kant, in his essay “What Is Enlightenment?,” from 1784, called on humanity to “Dare to know!” – and, seemingly, humanity responded to the challenge and truly dared to know. People acquired knowledge, and that in turn enabled them to cast off the “yoke of immaturity” (in Kant’s words) that they had brought upon themselves, and thus transformed themselves into secular folk. The most knowledgeable among them became atheists, of course.

This story, which is no more than the genealogical myth of the Enlightenment (“We were slaves until science released us into freedom with strong rationality and outstretched empiricism”), cannot explain completely the secularization process, nor why the concept of the necessity of God for a life of reason and morality is fading. In fact, the notion that knowledge cancels out belief is superficial even according to its advocates’ points of departure – for those who propose it will be the first to admit that human beings are capable of believing any nonsense, irrespective of what they know or don’t know. If new pieces of information were sufficient to unravel our long-held beliefs, we would switch worldviews in rapid succession.

Nor will it help if we assume that only authoritative and definitive knowledge will alter our views about the world, for knowledge of that sort has been available to humanity since ancient times. The Aristotelian, kabbalist or Buddhist worldviews presented “authorized” knowledge about the world and all that is in it, but it goes without saying that not every person who encountered those approaches has been persuaded and adopted them. Something more is needed to alter our fixed assumptions about reality; a good reason is needed for us to part with old premises and adopt new ones, and that reason cannot emanate from the new premises themselves.

Submission to Tradition

The foundations of the Enlightenment lie in the denial of the authority of tradition and the empowerment of humanity to the point of its becoming the supreme authority in every matter. Even before people turned to other structures of meaning, the self-evident awe of the Church – the inherent submission of Westerners to tradition – had been called into question. At the end of the fourth century, Augustine, one of the Church fathers, asserted that he “would not believe in the Gospel myself if it were not for the authority of the Catholic Church.” And at the beginning of the 18th century, the deist Matthew Tindal stated that “Reason was given to bring them [i.e. humanity] to the knowledge of God’s will” – and that nothing more is needed.

The foundations of the Enlightenment lie in the denial of the authority of tradition and the empowerment of humanity to the point of its becoming the supreme authority in every matter. Even before people turned to other structures of meaning, the self-evident awe of the Church – the inherent submission of Westerners to tradition – had been called into question. At the end of the fourth century, Augustine, one of the Church fathers, asserted that he “would not believe in the Gospel myself if it were not for the authority of the Catholic Church.” And at the beginning of the 18th century, the deist Matthew Tindal stated that “Reason was given to bring them [i.e. humanity] to the knowledge of God’s will” – and that nothing more is needed.

These two important thinkers believed that God’s existence was clear and self-evident, and neither dreamed of becoming an atheist. However, each of them shaped their religious world on the basis of loyalty to a different source of authority. For Augustine, the tradition does not only imbue faith with form and content, but it also validates it. For Tindal, not only are the interpreters of the tradition irrelevant, the tradition itself is of no relevance. God’s will is determined only according to reason, which is viewed as innate and universal.

The preference for reason antedates the loss of faith. Deism – a framework that grounded religion in reason and swept through the educated elite of Europe and North America in the 18th century – severed itself from the tradition and authority of the Church but not from belief in God. “O mighty God, I believe!” Voltaire, the champion of the French Enlightenment cried out – but added, “As to Monsieur the Son and Madame his mother, that is another matter!”

The preference for reason antedates the loss of faith. Deism – a framework that grounded religion in reason and swept through the educated elite of Europe and North America in the 18th century – severed itself from the tradition and authority of the Church but not from belief in God. “O mighty God, I believe!” Voltaire, the champion of the French Enlightenment cried out – but added, “As to Monsieur the Son and Madame his mother, that is another matter!”

When reason becomes a source of authority, tradition can be called into question, and after reason is adopted as a source of authority, God’s existence can also be called into question. However, it’s important to understand: This additional stage is not a “natural” progression, another step on the path along which all those loyal to reason will tread. After all, for deists like Tindal and Voltaire, reason actually pointed to God’s existence in no uncertain terms. “It is perfectly evident to my mind that there exists a necessary, eternal, supreme and intelligent being. This is no matter of faith, but of reason,” Voltaire wrote. Simple, isn’t it?

To shift from certainty of God’s existence to denial that God exists we need another step, in which reason is directed against God. The question is, what impels reason to deny that God exists. The answer to that question is found not in the factual realm but the normative one.

Reason is God’s Image

The transition from traditional Christianity to deism stemmed from a moral reading: For the deists, rejection of the belief in miracles or in divine revelation was a matter of preserving human dignity. Let us return to Matthew Tindal (1657-1733). An English deist, Tindal was one of the most influential thinkers of the 18th century. In his 1730 book “Christianity as Old as the Creation,” which was accorded the status of a deist holy scripture, he dwells on the universal principles of religion and explains how “true” Christianity is perfectly rational.

For Tindal, human reason “for kind, though not for degree, is of the same nature with that of God’s; nay, it is our Reason which makes us the image of God himself.” Human beings are rational because they were created in the image of God. Otherwise, how could they even think? However, precisely because of this, the debasement of reason is an affront to human dignity: “Without this precedent Enquiry, our Belief… were to overthrow all the Laws of Nature, to Debase the Dignity of Mankind, and to efface the Image of God implanted in us.”

According to Tindal, to cling to reason is to cling to the image of God, and to stray from it is to debase it. It follows that to reject superstition (miracles, the virgin birth, and so on) is to preserve God’s image and therefore also to worship God. Thus, if in the past faithfulness to the image of God inculcated in humanity was achieved by refraining from sin and by obeying God, for Tindal faithfulness to God’s image is achieved by rejecting superstition, which from his perspective include what in the past were considered holy tenets of belief.

Tindal’s book generated a broad controversy in Europe, and more than a hundred essays were written in an attempt to refute his arguments. Of course the Church, which itself was viewed by Tindal as a debasement of rational faith, attacked him. However, notwithstanding his struggle against the Christian tradition, Tindal never for a moment denied that God existed. On the contrary, he thought that without God we would not be rational beings.

Deists as Cowards

Just as Tindal sought to preserve human dignity, the first European thinkers who explicitly advocated atheism thought that belief should be rejected not because it was wrong but because it was an infringement of human dignity. A case in point is Paul-Henri Thiry d’Holbach, a leading figure of the French Enlightenment. He devoted his life to a struggle against religious belief and to the dissemination of atheistic thought. He financed the translation of essays, wrote more than 50 books, supported artists and young thinkers and established in his home a debating club for the Parisian intellectual elite, which became one of the important social institutions of the French Enlightenment.

Just as Tindal sought to preserve human dignity, the first European thinkers who explicitly advocated atheism thought that belief should be rejected not because it was wrong but because it was an infringement of human dignity. A case in point is Paul-Henri Thiry d’Holbach, a leading figure of the French Enlightenment. He devoted his life to a struggle against religious belief and to the dissemination of atheistic thought. He financed the translation of essays, wrote more than 50 books, supported artists and young thinkers and established in his home a debating club for the Parisian intellectual elite, which became one of the important social institutions of the French Enlightenment.

D’Holbach was contemptuous of the deists and considered them cowards. From his point of view, they had gone only halfway and had not taken the use of reason as a criterion for examining religion to its logical conclusions. Although they sanctified reason, they did not cast off the final superstition – the source of all superstitions: the belief in the existence of God.

In the last lines of his most important book, “The System of Nature,” D’Holbach urges us to “inspire the intelligent being with courage; infuse energy into his system, that, at length, he may feel his own dignity.” D’Holbach wishes to augment reason and protect its dignity by rejecting all that is in opposition to it. As such, he seeks to preserve our dignity as human beings. Atheism, he maintains, is based on nature and on reason, no less and no more. It’s logical. We need only look at the facts unflinchingly. Regrettably, he notes, this minor condition is sufficient to prevent most people from becoming atheists, as they lack the courage to face the facts.

Unlike Tindal, for D’Holbach human dignity arrives not from protecting God’s image within, but from rejecting the very idea of the image of God and of God himself. Human dignity derives from sheer adherence to reason, from the decision not to surrender to comforting illusions and from mustering the courage necessary to those ends. A person’s reason shows them the truth and they are faithful to it and are not tempted by consoling beliefs. Sheer insistence on the truth imbues one with dignity.

God as a Threat

What leads to D’Holbach’s additional step beyond the deist position? It would be very easy to accept his account: The deists, all their education notwithstanding, lack sufficient courage, whereas he and atheists like him are not afraid to cope with either society’s vilifications (and, in their time, also the concrete danger to their well-being) or with the heartrending separation from the fictions to which they had become accustomed.

However, this answer, which remains popular to this day, misses an important element in the movement from belief to non-belief, an element that also constitutes a deep dimension in the development of the secularization process: the ethical element. This is a story at whose center stands our relationship with reason.

With the advent of the modern era, human reason ceases to be perceived as a reflection of the existing world/divine order (the logos, God’s laws, God’s wisdom) and becomes a private, procedural matter, a mode of thought. Descartes is a pioneering thinker in this transformation. For him and for his successors, to be rational means to think according to certain standards, and not to act according to the rationality that is ostensibly implanted in the universe. In plain words, reason moves exclusively to become located in the individual’s interiority.

However, as with Tindal, at this stage reason remains connected to and dependent on God: For Descartes and others, reason is God’s image in humanity. Only in the course of the 18th century is reason gradually severed from divinity and becomes exclusively a human capability. Reason changes together with the rise of individualism and becomes a human aptitude.

It is here that the significant transformation arrives: Humans’ self-perception as being disconnected from their surroundings and as autonomous, leads to this autonomy itself being morally charged. Reason is not only an efficient tool, but a value. The ability to think alone, precisely, clearly and impartially, is now a virtue to be preserved and cultivated. Our rational autonomy becomes an ideal. In plain words: Autonomous thinking is now a moral action.

In his book “Sources of the Self,” the Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor explains that the next, critical, stage arrives when the connection with divinity is transformed from being a necessary condition for morality into an obstacle to morality. This happens when the dependence on divinity, or even its very existence as a higher authority, threatens human autonomy and humans’ ability to arrive at moral decisions. Not only is the inner imperative crucial, but one must not accept a reality in which that imperative can be overridden by an external authority. Think about it: If autonomy is a condition for morality, and is a value unto itself, everything that undercuts it constitutes a moral wrong and even subverts the basis of morality. This is the precise point at which God is transformed from being the necessary condition for every moral system into being the greatest danger to morality.

In his book “Sources of the Self,” the Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor explains that the next, critical, stage arrives when the connection with divinity is transformed from being a necessary condition for morality into an obstacle to morality. This happens when the dependence on divinity, or even its very existence as a higher authority, threatens human autonomy and humans’ ability to arrive at moral decisions. Not only is the inner imperative crucial, but one must not accept a reality in which that imperative can be overridden by an external authority. Think about it: If autonomy is a condition for morality, and is a value unto itself, everything that undercuts it constitutes a moral wrong and even subverts the basis of morality. This is the precise point at which God is transformed from being the necessary condition for every moral system into being the greatest danger to morality.

“Materialism as it appears in the 18th century… is no mere scientific or metaphysical dogma; it is, rather, a moral imperative,” the German-Jewish philosopher Ernst Cassirer (1874-1945) writes. The individuals forged by the Enlightenment saw themselves as moral subjects only on the condition that their decisions were autonomous and free. They were unwilling to accept a moral authority that threatened their autonomy, or that was above it. Their problem with a supreme authority wasn’t only that it would affront their pride, but also that it would affront their morality, their possibility to be ethical. Thus, from the loftiest motives, human beings reached a state in which it was no longer only possible, but now also morally essential, to reject God’s existence.

The Ethos of Atheism

If for Tindal at the end of the 17th and start of the 18th centuries, our human dignity depends on our rejecting superstitions that debase our reason (which is the image of God), for D’Holbach, in the second half of the 18th century, human dignity is no longer the derivative of a divine gift. On the contrary: Dignity is preserved through the denial of all belief in a divine gift, through not bowing to the temptation of the beliefs, to the illusory consolation of religion.

D’Holbach presents a modern concept of self-respect that stems from the individual and is measured according to human criteria. Human dignity was not bestowed on us by God and does not depend on following God’s precepts. One’s dignity is actually dependent on the preservation of independence (conceptual, practical) and on remaining loyal to one’s principles. Man is not God’s image and is not divine or spiritual at all. However, self-respect can be preserved by acting in accordance with the precepts of morality and reason – which spring from within the individual.

Without a doubt, the increasing popularity, beginning in the 18th century, of the worldview represented here by D’Holbach owed not a little to the scientific revolution – to the proven ability of the scientific method to explain nature and to base technological developments on those explanations, and to the creation of a realm of knowledge that is not religion-dependent. However, those developments themselves, although creating the possibility, did not obligate D’Holbach (or anyone else) to deny the existence of God and to maintain that the source of our reason is natural and not divine. What obligated D’Holbach to do so was the moral imperative he formulated, which rested on the transference of the source of human morality and dignity from loyalty to God, to loyalty to oneself.

D’Holbach rejects God’s existence not because he has proof that God does not exist, but because for him belief in God’s existence is an affront to human dignity. Belief in God, or in any religious dogma, means sacrificing a crucial dimension of what makes us human, of what imbues us with human dignity and enables us to make moral decisions. According to D’Holbach, and according to increasing numbers of people from the intellectual elite of his era, believers have give up their reason and their free choice. More than any specific scientific discovery, it is this stance that undermined religious belief fundamentally.

Control of Control

The Enlightenment sought to facilitate and advance people’s self-control vis-a-vis themselves and their world. From self-control comes also control over knowledge and over consciousness. However, the next stage must be also control over the control. Enlightened individuals want to entrench and ensure their control, and therefore they are compelled in the final analysis to reject the existence of God – for nothing threatens that control more than an eternal father figure with infinite powers. “The first revolt,” asserts the anarchist thinker Mikhail Bakunin, “is against the supreme tyranny of theology, of the phantom of God. As long as we have a master in heaven, we will be slaves on earth.” To move from slavery to freedom, it is necessary to deny God’s existence. That is the Exodus from Egypt for modern people.

The thinkers cited above represent an illustration of a general cultural shift, in the framework of which Western humanity turned against the existence of God, and did so out of ethical motives. God’s image, which was internalized and became reason and free will, coalesced as an alternative moral source to God. Reason became an autonomous ethical framework, not dependent on God’s existence. Subsequently, reason, which already makes possible a rich normative system (autonomy, self-respect), must reject the existence of God, on the basis of an ethical stance: God’s existence is not moral, because God is injurious to morality; God sabotages the possibility of being autonomous and possessing self-respect.

The rebel, Albert Camus writes in his book of the same title, “defies more than he denies” God. And Camus is indeed defiant. “The absurd man,” he writes in “The Myth of Sisyphus,” sees only “collapse and nothingness. He can then decide to accept such a universe and draw from it his strength, his refusal to hope, and the unyielding evidence of a life without consolation.” The defiance, the courage, the dignity and the transcendence that stem from an uncompromising coming to terms with nullity – it’s all here. A direct line leads from D’Holbach to Camus and from Camus to a contemporary atheist like Richard Dawkins, who writes, “The atheist view is… life-affirming and life-enhancing, while at the same time never being tainted with self-delusion” (from “The God Delusion”).

The rebel, Albert Camus writes in his book of the same title, “defies more than he denies” God. And Camus is indeed defiant. “The absurd man,” he writes in “The Myth of Sisyphus,” sees only “collapse and nothingness. He can then decide to accept such a universe and draw from it his strength, his refusal to hope, and the unyielding evidence of a life without consolation.” The defiance, the courage, the dignity and the transcendence that stem from an uncompromising coming to terms with nullity – it’s all here. A direct line leads from D’Holbach to Camus and from Camus to a contemporary atheist like Richard Dawkins, who writes, “The atheist view is… life-affirming and life-enhancing, while at the same time never being tainted with self-delusion” (from “The God Delusion”).

Their successors in Israel are columnists like Uri Misgav, from Haaretz, who thinks the problem is lack of knowledge, and thus wrote that “many Israelis believe there is a God, because no one ever offered them an alternative – that there is no God”; or Rogel Alpher, also from Haaretz, who praises directness and adherence to the truth as he writes that belief in God “is such an ignorant mistake, that it partakes of stupidity and mental disorder… It’s necessary to speak truth and stop trying to curry favor. There is no God and to believe in him is stupidity.”

Note well: Among atheists, too, there has been a decline over the generations. D’Holbach and Camus still laud the ethos of atheism, the need for self-transcendence and moral faithfulness, with a lucid vision and with self-respect. Their contemporary successors are so far from the point of conception of the atheistic tradition, that they make the mistake of thinking that the problem with believers is only lack of knowledge or absence of wisdom. They forgot the tenets of non-belief.

Moreover, there’s a limit to the effectiveness of calling religiously observant people ignorant or stupid. What the atheist of the vocal strain doesn’t get is that it’s not knowledge that those who believe in God lack, and that it’s not “mental disorder” that underlies religion. Placing God above humanity gives one direction and meaning – elements that humans need far more than information. Only when the conditions matured for extracting alternative direction and meaning, was atheism able to expand into wider circles. Only when that direction and that meaning required the rejection of God could atheism become synonymous with courage and self-respect. And only if direction and meaning will be provided today, will atheism be able to go on gaining adherents. Making atheism shallow to the point where it mocks the believers misses its essence and diminishes its formative revolution.

The acceptance of atheism, and in fact the entire secularization process, are deeply entwined with the process of the individuation of Western man. From being the source of reason, dignity and goodness, God becomes an external authority that does not enable an autonomous, moral, dignified life. After God’s image, as an idea, was internalized, God himself, this time as a moral source, was internalized. And if God is internalized, there is no longer room for him externally, in the objective field. The kingdom cannot be divided between two Gods. That’s how monotheism works. Faithfulness to the inner moral imperative requires the rejection of an external moral imperative. That’s how secularization works.

—

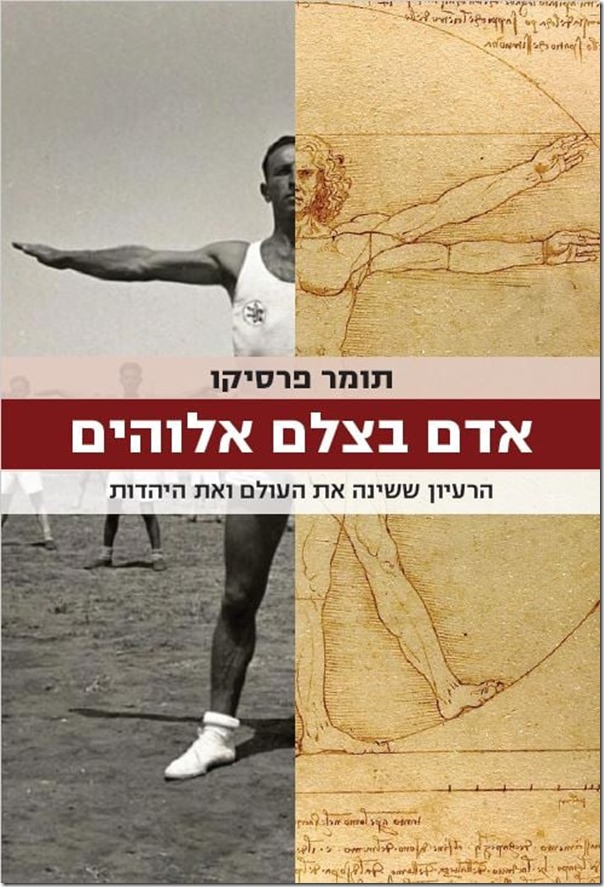

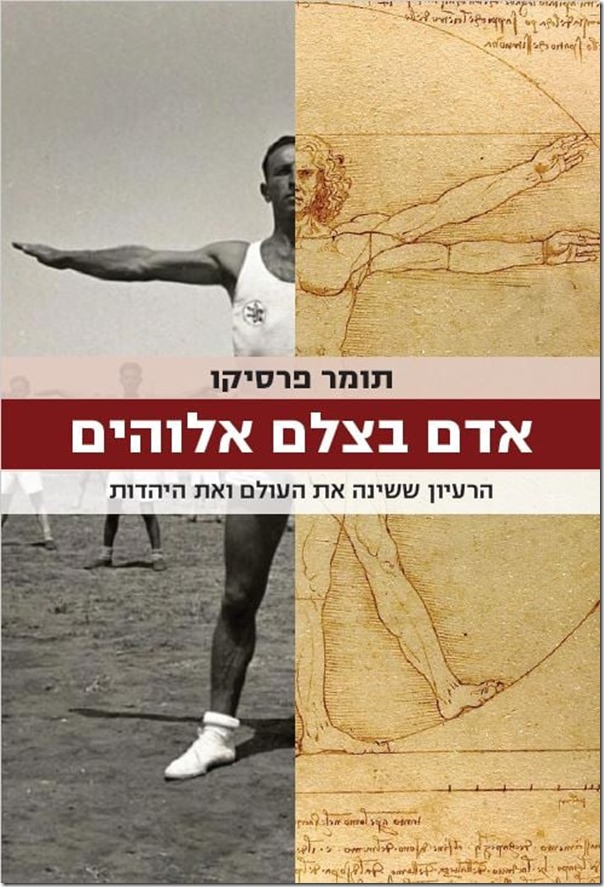

This article, published in Haaretz, is based on a chapter in my newly published book “Man in God’s Image: The making of the Modern World” (Hebrew).