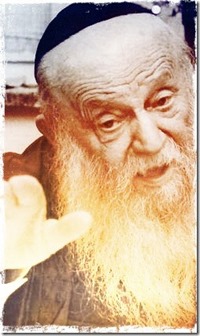

There is one primary, general thing: the state. It is all holiness and without flaw. It is a supreme heavenly manifestation of ‘he who returns the divine presence to Zion.’ – Zvi Yehuda Kook

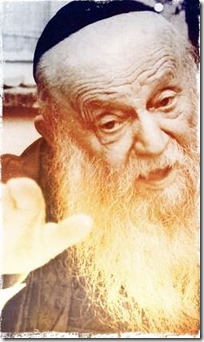

Holiness is to religion what blood is to the human body. It impels the religious organism. It is the soul’s desire and the heart’s reverence. It was not by chance that when religion officially became a field of academic research, at the end of the 19th century, the fathers of the field, distinguished scholars like Emil Durkheim and Rudolf Otto, sought to define “holiness.” Is it the restricted, the forbidden, or perhaps the moving and the awe-inspiring? Is it the inaccessible, the remote, or precisely the innermost and intimate? Or perhaps both the one and the other are emanations of the holy of holies? Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook honed it down to one: The holy is the political. The state is holiness. Being holy, it is perfect. Being holy and perfect, it is the divine chariot to which the horsemen of the redemption are harnessed.

To treat these ideas dismissively, or fearfully, is to miss their depth. The process undertaken by Zvi Yehuda Kook, who himself functioned as the interpreter of the thought propounded by his father, Rabbi Abraham Isaac Hakohen Kook, was not only daring but brilliant in its revolutionary character. The perception of the State of Israel – the political, bureaucratic, legal, secular corpus – as an entity that is “entirely holiness,” posed a tremendous challenge not only to the intentions and wishes of the state’s founders, and not only to the self-perception of its citizens. It was a direct assault on the very secularization of the Jewish people. Accordingly, Gush Emunim (or, Bloc of the Faithful), the operational arm of these ideas, functioned as a spearhead with which Zvi Yehuda assailed secularization itself. The failure and crumbling of Gush Emunim thus sounds the knell of defeat for the last Jewish attempt to overcome the secularization process.

To treat these ideas dismissively, or fearfully, is to miss their depth. The process undertaken by Zvi Yehuda Kook, who himself functioned as the interpreter of the thought propounded by his father, Rabbi Abraham Isaac Hakohen Kook, was not only daring but brilliant in its revolutionary character. The perception of the State of Israel – the political, bureaucratic, legal, secular corpus – as an entity that is “entirely holiness,” posed a tremendous challenge not only to the intentions and wishes of the state’s founders, and not only to the self-perception of its citizens. It was a direct assault on the very secularization of the Jewish people. Accordingly, Gush Emunim (or, Bloc of the Faithful), the operational arm of these ideas, functioned as a spearhead with which Zvi Yehuda assailed secularization itself. The failure and crumbling of Gush Emunim thus sounds the knell of defeat for the last Jewish attempt to overcome the secularization process.

This fundamental defeat did not come about without there being vast achievements along the way. In the course of its existence, Gush Emunim, which was one of the largest and most important messianic movements in Jewish history, succeeded in changing completely, perhaps for many years to come, the life of all the people living between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea. The movement revitalized the religious-Zionist community, which until then had been little more than a religiously observant annex of Labor-based Zionism. It put forward a riveting vision that integrated divine promise and human sovereignty, while the attempt to implement it engendered far-reaching political, geographical and demographic changes. Testimony to its importance can be found in the withering conceptual-social void that remained after its collapse.

Nothing better signifies the death of the Kookist vision – the driving ideological force behind Gush Emunim – than the tenure of Naftali Bennett as the head of the national-religious party. Kookism (to use the term coined by sociologist-anthropologist Gideon Aran, who has studied the movement) purported to provide an overall narrative framework that reinterprets reality and explains how it is precisely the elements that seem to directly contradict halakha, Jewish law, that actually carry the message of redemption and realize its most exalted vision.

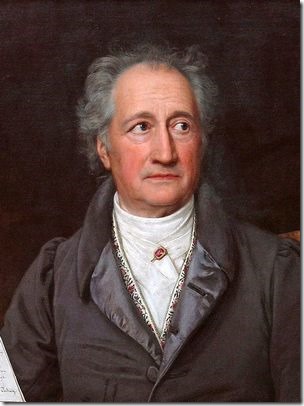

In the view of Abraham Isaac Kook (1865-1935), known universally as Rav Kook, and in complete contrast to other ultra-Orthodox, or Haredi, rabbis, secular Zionism bore in its national backpack the harbinger of the messiah. The Zionists might desecrate the Sabbath and irreverently ignore halakhic sexual codes, but according to the historical dialectic envisioned by Rav Kook, after returning from exile and establishing a Jewish state, the “sons of the insolent ones” will return to the tradition and cling anew to the biblical covenant between God and the Jewish people. At that point, the aberrant subversion of the tradition’s tenets will metamorphose into a synthesis in which the vision of the redemption will be wholly realized in the form of a state that manifests perfectly the Jewish messianic ideal. Simply put, though the Zionists think they are establishing a secular nation-state, the cunning quality of divine wisdom guides them to actualize the prophecy of the end of days.

The Birth of Religion and State

It’s important to understand that Rav Kook reinterpreted not only secular Zionists, but also secularism itself. To fully grasp the revolutionary depth of his theology, we need to look at the development of the secularization process and the inner logic it embodies. In contrast to the popular assumption, the crux of the secularization process is not the loss of faith and the abandonment of religious ritual, though they are of course significant features. What underlies secularization is a redistribution of the public space, and a differentiation between diverse dimensions of human activity.

Until the modern age, religion cast its net over a wide range of human activity (for example, education, art, policy, knowledge and morality). However, during the past few centuries, initially in Europe, these realms were expropriated from religion and placed in the hands of distinct systems – the state, scientific research and the human conscience – that specialize in applying them, each in its own way.

Moreover, religion itself was narrowed, and became a defined and confined area of our life. We can be members of a particular nationality, part of a specific social class or group, engage in one or another profession, jog or play chess as a hobby – and also be religious. Or not religious. From its status as the cornerstone of our identity, the foundation of our worldview and of our self-perception, without which we are lost and for which we will be prepared to lay down our lives, religion became a category, one issue among many in our lives. We have the option to add it as another thread in the fabric of our identity – or not. That is the deep meaning of secularization.

The distinction between the “religious” realm and the realm devoid of religious significance is not self-evident. In fact, it is nonexistent in the world of many religious traditions. Judaism and Islam, for example, do not distinguish between a space that is saliently under the control of religion, with its institutions and its principles, and other realms that are unconnected to religion. These two traditions were historically all-encompassing social frameworks that sought to embrace every aspect of life: from the form of the regime to the social classes, from agriculture to an individual’s breakfast.

It’s in Christianity that we find a clear-cut differentiation between the different spheres. Beginning with Jesus’ words to his disciples, “Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s” (Matthew 22:21), a clear distinction is put forward between the religious realm and the political realm, which is considered secular. That distinction accompanied the Western world in its development, with the tension between the religious authority (the pope) and the secular authority (the various emperors of Europe) often constituting fertile ground for struggle.

This differentiation laid the foundation for the secularization process. Beginning in the 17th century, together with the consolidation of Protestant Christianity, a confluence of developments increasingly diminish the religious sphere, with the aim of confining it to the individual’s psyche. The public sphere is defined as “secular,” that is, void of religion. Furthermore, the perception of religion as one’s personal affair develops in tandem with the perception of the social space as the public affair of the populace.

The more religion is compartmentalized into the depths of the individual’s psyche, the more the individual becomes part of a collectivity that is not religious but national. Hence the birth of the citizen – the autonomous individual who is above all a human being, who decides his religious beliefs for himself and chooses his form of government together with his fellow citizens. The nation-state, and subsequently the democratic state, spring up as part of the secularization process, and are defined parallel to and dependent on the modern definition of religion.

For Judaism, therefore, secularization constituted a challenge not only because it brought about the Jews’ mass abandonment of the observance of the commandments, but because it utterly undermined the structure of Jewish identity. If until the 18th century, the Jews perceived themselves, and were perceived by others, as a separate ethno-religious community (like the Druze today, for example), the emancipation – the Jews’ transformation into citizens – obliged them to redefine their Judaism.

As Jewish studies professor Leora Batnitzky notes in her book “How Judaism Became a Religion” (2011), the Jews, the absolute majority of whom lived in Europe before World War II, responded to these developments in diverse and contradictory ways. Whereas modern Orthodoxy, Reform Judaism and Conservative Judaism defined Judaism as a religion, Zionism perceived it as a nationality.

The religious movements held that Judaism is a ritual belief system that is limited to the individual realm, and endeavored to show that no contradiction is involved in a person’s being “a German of the Mosaic faith,” namely a German by nationality, and a Jew by religion. The Zionists, in contrast, rejected the religious-belief dimension of Judaism as an anachronistic excess to be discarded, and viewed Judaism primarily as a nationality. As such, it was up to the Jews to establish a state of their own, and it was only natural that the state the Zionist movement had in mind would be secular and democratic. In such a state, Jews, if they insisted, could be “religious,” though they would restrict their occupation with that archaic matter to their home and congregation. The public space would be based on the national disposition: It would be secular.

Undermining Secularism’s Essence

Back to religious Zionism. It began with the Mizrachi movement of Rabbi Yitzhak Yaakov Reines (1839-1915), but without challenging the modern division of Judaism into religion and nationality. Reines allied himself with Herzlian Zionism, with the aim of providing the Jews a safe haven in the Land of Israel. In terms of his attitude toward secularization, there is no difference in principle between Hamizrachi and modern Orthodoxy in Germany, France or the United States. Reines, we can say, simply dreamed of Israelis of the Mosaic faith.

Rav Kook’s doctrine presents an essentially different approach: He intended explicitly to overcome the disparity between religion and nationality by uniting them in messianic matrimony. Kook envisioned a “state that is in its essence ideal”: meaning, a state that exists as a divine representation, implementing God’s will on earth. There is no place for secular individuals in such a state, because the connection between upper and lower is the basis of its existence, the source of its vitality and efflorescence and, no less, of its political platform. Amid attempts (that failed) to establish Degel Yerushalayim, a religious political movement, Rabbi Kook wrote, “with a supreme show of shining, free holiness, we shall illuminate all regime-based paths.” Politics will be nourished by holiness; holiness will become political.

Rav Kook’s intention was to annul every vestige of the secularization process. He was fiercely critical of the Orthodox Jewry of his time, which he perceived as occupied with a “religious idea,” by which he meant that it viewed Judaism as mere religion. For Kook, however, Judaism was a “divine idea” that encompasses the universe in its totality and views the Jewish people as a uniform organism that functions as an expression of the supreme will. It was Judaism’s division into a religion, on the one hand, and a nationality, on the other, that he rejected outright: “It is a great error on the part of those who do not feel the immanent unity of Israel … from this derives the desire to dichotomize the national matter and the religious matter into two parts.” Judaism is “one indivisible unit,” and the state that will be established is wholly sanctified unto God. The whole earth is filled with his glory.

Rav Kook did not live to see the sovereign State of Israel, and if he had, it’s difficult to know what he would have thought of it. In its first decades of existence, Israel was blatantly national and vigorously secular. Its leaders did not regard themselves as the receptacle of the divine inspiration and did not ground its regime in “shining holiness.” Rav Kook’s doctrine was updated and adapted to the Israeli situation by his son, Rabbi Zvi Yehuda, and his pupils. They would lead Gush Emunim after the conquest of Judea and Samaria and would implement with a mighty hand what they learned under the tutelage of their mentor.

The Roots of Gush Emunim

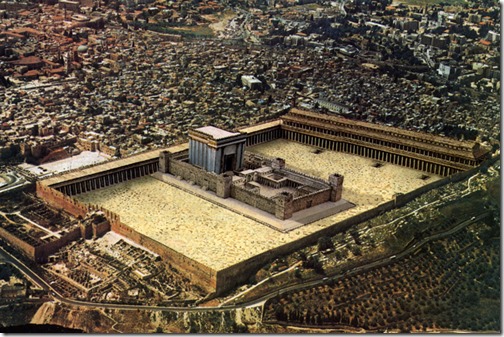

The heart and core of Kookism is the desire to unite two holy entities: the Land of Israel and the State of Israel. The holiness of the land derives from the Torah and tradition. The holiness of the state is gleaned from Rav Kook’s assertion that the present configuration of Jews in Israel augurs the advent of the redemption. The messianic, as usual, serves as an alchemical transformer that turns everyday brass into redemptive gold. In practice, the State of Israel rules in the Land of Israel and imprints the will of the Jews on it. The popular will – an important Kookist principle – is an expression of God’s will. Thus, for Kookism, sovereignty, as the political expression of the popular will over the land, is of special importance. “Redemption is but sovereignty: the people’s government across the whole span of its land,” stated Zvi Yehuda. The Land of Israel, under the people of Israel, according to the will of Israel, which advances (even unconsciously) the Torah of Israel.

And, as it happened, Israeli sovereignty over the “whole span” of the land came to pass after the Six-Day War. Only then were the holiness of the state and the holiness of the land fused together perfectly. As the poet Natan Alterman put it, “This victory … effectively erased the difference between the State of Israel and the Land of Israel.” For the disciples of Zvi Yehuda, this territorial expansion was not only an expression of God’s will but the realization of his father’s political theology.

And the territorial expansion itself became a ritual for them. What occurred, in the words of Gideon Aran, was “a kabbalization of Israeli nationalism, and in its wake a ritualization of political activism, making it possible to bring Zionism to its final conclusion, and at the same time disarm it of its practicality and absolve it of its responsibility, which are the basis of its historic revolutionism.” The act of settlement becomes a ritual, and messianic belief allows settlement of the land and Israeli sovereignty over it to be seen as the force that turns the heavenly gears of the divine machine. In Aran’s incisive phrasing, it’s the metamorphosis of religious Zionism into the Zionist religion. No longer is there the religious element within Zionism; now there is the overriding religious framework, which is characterized in part by Zionism.

There is a controversy over the roots of Gush Emunim. Aran, who as a researcher skittered across the rocky slopes of Samaria with members of the movement, locates its gestation among the Gahelet (“ember”) group of young people (among whom were Haim Druckman, Zephaniah Drori and Zalman Melamed, all of whom became prominent rabbis). Seeking a response to Israeli secularization, they moved into the half-empty yeshiva of Rav Kook, which was then led by his son.

There is a controversy over the roots of Gush Emunim. Aran, who as a researcher skittered across the rocky slopes of Samaria with members of the movement, locates its gestation among the Gahelet (“ember”) group of young people (among whom were Haim Druckman, Zephaniah Drori and Zalman Melamed, all of whom became prominent rabbis). Seeking a response to Israeli secularization, they moved into the half-empty yeshiva of Rav Kook, which was then led by his son.

Avi Sagi and Dov Schwartz, arguably the most distinguished researchers of religious Zionism, believes that the Gahelet group simply rode the coattails of a grass-roots movement that had begun without them, to appropriate it. They find the birth of Gush Emunim as taking place among circles of well-off, middle-class, young Orthodox people who embarked on settling Judea and Samaria not for reasons of redemptive theology but as compensation for an inferiority complex they suffered vis-a-vis secular Zionism, and as the expression of a quite standard pioneer-Zionist ideology. They simply took advantage of their opportunity to become pioneers and “fulfillers.” It was only afterward that they referenced Rav Kook’s visions in order to explain to themselves and others how their actions could be reconciled with the general Jewish messianic program. Their action, however, enabled and encouraged the Gahelet rabbis and other Kookists to take over the movement and to turn it gradually into a messianic theological force.

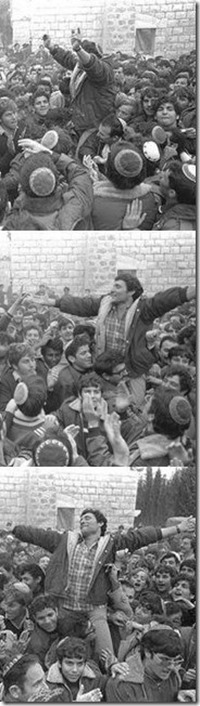

Gush Emunim was established at the beginning of 1974, just a few months after the Yom Kippur War. Graduates of Merkaz Harav Yeshiva in Jerusalem – among them Moshe Levinger, Haim Druckman, Yoel Bin Nun and Hanan Porat – met in Kibbutz Kfar Etzion, in the West Bank’s Etzion Bloc, which was captured in 1967, and drew up a vision for a national and religious movement of awakening. The scale of the vision was as impressive as it was all-inclusive. Its goal was nothing less than full redemption for the Jewish people and the whole world. It accommodated the increasing closeness of secular Jews to the world of religious precepts – the synthesis envisioned by Abraham Isaac Kook.

As for Israeli sovereignty over Judea and Samaria, it was irreversible, according to an unequivocal pronouncement by Zvi Yehuda Kook. “The State of Israel is a divine matter … Not only are there no withdrawals from kilometers of the Land of Israel, heaven forbid, but on the contrary, we will add conquests and liberations … In our divine structure, which is comprehensive and world-embracing, withdrawal has no reality and no grip,” he stated. Gush Emunim would be the earthly manifestation for this redemptive momentum. Or, in the words of the late Hanan Porat, “Gush Emunim is the yearning for God’s manifestation in the world.”

Gush Emunim proceeded to establish the settlements of Ofra and Kedumim, and tried repeatedly to establish Elon Moreh. In 1977, Menachem Begin assumed power, promising “many more Elon Morehs,” and was as good as his word. Beit El, Elkana and Kfar Adumim were established. The success necessarily generated institutionalization. In 1979, the Amana movement was created in order to organize the settlement project bureaucratically and economically. The following year, the Yesha Council was formed – an administrative body that amalgamated the heads of the local authorities in Judea, Samaria and Gaza (for which Yesha is an acronym). Thus, by the end of the 1980s, having consolidated formally and bureaucratically, Gush Emunim had taken on institutional trappings and effectively ceased to be a living ideological movement.

Secularizing the Messiah

Gush Emunim continued to fade, but it would be a mistake to view its decline as a simple matter of “bourgeoisification.” Of course, like every movement of spiritual awakening, it too passed through a youthful stage and entered life’s more formalized paths. However, its disintegration was above all the increasing unraveling of the Kookist paradigm. Though this occurred concurrent with the turn to the bourgeois of Gush Emunim, it was not because turning bourgeois signifies institutionalization, but because its deep meaning is secularization.

Kookism viewed Zionism as a national-religious totality that would fulfill the divine messianic plan. The act of land settlement became ritualized; redemptive significance was attributed to the application of Israeli sovereignty to more and more territory. But what happens when settlement is implemented not by a group of messianic activists but by a commercial company? And what results from the quest by the settlers themselves not for the act of settlement as such but for quality of life in spacious homes with red-tiled roofs?

During the 1980s, and with greater intensity in the 1990s (and precisely during the tenure of Prime Minister Rabin, who greatly improved the infrastructure in Judea and Samaria), the settlement enterprise became a lodestone for people in search of housing solutions and upgrades. The settler, even if he had an ideological past, ceased to be a pioneer and became, in practice and in substance, a consumer.

Settlers who solicit funding and infrastructure from the state view it as a service provider, not as a manifestation of the Shekhinah (the divine presence). Though not necessarily contradictory, these two approaches generate a different religious consciousness. The Kookist vision of a unity of religion and nationality is inherently idealistic and cannot readily accommodate an instrumental approach that is out to use the state and not to worship it. Activism gives way to routine, and routine institutionalizes a relationship underlain by an aspiration that aims at preservation, not breakthrough. The settler becomes accustomed to receive, not to create, and the settlement ritual is normalized. The unity between national land settlement and religious ethos is degraded; the two revert to being two separate facets of the quotidian.

Hence the return to the picture of the basic differentiation within the secularization process. The Zionist religion reverts to being religious Zionism – namely, an approach that identifies the state with national Judaism, and religion with halakhic Judaism. Routine vitiates Kookism. Without the messianic vector that demands movement deriving from constant tension, Kookism becomes one more form of exegetical theology that offers reassuring answers to queries about belief. Bourgeoisification secularizes Kookism and deconstructs it into standard religious Zionism.

Two elements accelerate this basic process of re-secularization. The first is the unwillingness of secular Jews to become religiously observant. The Movement for Greater Israel, established after the Six-Day War, showcased a highly impressive collection of secular Israelis (Haim Gouri, Natan Alterman, Aharon Amir, Moshe Shamir and others). Here, according to Gush Emunim, was proof of the advent of Rabbi Kook’s vision: Direct contact with the territories of the homeland had seemingly awakened the “Jewish element” within these secular figures, and they were on their way back to the Torah.

The collapse of this hope undermined Kookist optimism. It also shows the fundamental unfeasibility of Kookism (or of any totalitarian religious ideology). The modern world is too diverse and complex, and its inhabitants subscribe to a concept that is too individualistic and autonomous to be subsumed within a single dogmatic framework. Secularity is here to stay.

As if it were not enough that the people of Israel did not become penitents, since the 1980s, the State of Israel has repeatedly reduced its sovereignty over the territories of the Land of Israel. The withdrawal from Sinai, in the wake of the Israel-Egypt peace agreement, was the first serious blow to Kookist theology, followed by the withdrawals from the cities of the West Bank in the Oslo Accords and from the Gaza Strip in 2005. Kookist messianism, which categorically rejected any possibility of withdrawal, had to cope with recurrent contradictions in regard to the paradigm it espoused. They undermined it and ultimately caused it to crumble.

These three intertwined factors render the backtracking from Kookism to a simple national-religious conception – like that of Hamizrachi, the inceptive religious-Zionist ideology – almost inevitable. The bourgeois thrust transformed the attitude toward the state from ritualistic to realistic, and from idealistic to pragmatic. Due to the state’s secular character, it is looked on with growing reservations, even alienation. The courts become an obstruction, the country ruled at times by a “government of malice,” and not even the IDF is as holy as it was. When the state also initiates actions that flagrantly contradict Kookism, the alienation becomes blatant.

Religious Zionism in Israel has thus withdrawn to the stance of modern Orthodoxy. It has redivided reality into a secular realm and a religious realm, with the state considered a secular matter (with which it’s necessary to have dealings, and to try and draw as close as possible to the right values); while everything that takes place in its communities (in the religious education system, the youth movements and the synagogues as well) falls under the aegis of the Shekhinah. True, unlike Europe or the United States, this is the state of the Jewish people, but like them it is also a modern nation-state, and as such is based on secular logic that confines religion to a certain enclave and excludes it from rule in the fields of power and knowledge.

Nationalism as Secularisation

But the disintegration of Gush Emunim generated additional shock waves. The tendencies that began with the collapse of the Kookist worldview intensified. In the past decade, it’s become clear that religious Zionism has reached a new phase in its relinquishment of Kookist ideals. It has entered a stage that places a strong emphasis on the distinction between religion and nationality – in other words, on the intensification of secularity. These processes are related to the greater share that accrues to the national dimension in the identity makeup of religious Zionism: that is, the ethnic element and the right-wing political posture have become far more central than they were in the past.

Beginning in the 1990s, the National Religious Party became declaredly right-wing. The party’s “historic alliance” with Mapai, forerunner of Labor, went by the boards in 1977, but its existence before that attests to the NRP’s character at the time. Its pragmatic and dovish leaders, such as Yosef Burg and Zerach Warhaftig, were replaced by declared right-wingers such as Hanan Porat, Yitzhak Levy and finally Naftali Bennett. Its current incarnation as Habayit Hayehudi has brought the process to a peak. The party’s composition shows clearly that a right-wing stance is more important than a halakhic one: The party will take in secular right-wingers but has no place for religiously observant left-wingers.

Moreover, the national-religious party is no more than the image of its voters. In a comprehensive study conducted in 2014 under the auspices of the Israel Democracy Institute, political scientist Tamar Hermann and her associates found that among the broad circles of this public, a “political-security right-wing” approach is a more stable and more permanent common trait than a uniform, binding religious way of life.

In her study of ex-Orthodox Jews in Israel, Poriya Gal Getz quotes a former religiously observant individual as saying, “Even after I stopped being religious, the feeling is that parents and community will be hurt far more if you become a leftist, because that’s perceived as sheer treason.” Treason, understandably, is a move against one’s reference group, which embodies our primary identity traits. When the reference group is determined more according to one’s political stance than by halakhic strictness, the relative share of those elements in one’s personal identity becomes clear.

Here’s what the increasing secularization of religious Zionism looks like: Its adherents view themselves in the first instance as members of the Jewish people and defenders of the State of Israel. True, they also observe the commandments, but that’s just their “religion,” something they pile onto nationality that expresses their personal relationship with God. Their basic identity is ethnic-Jewish and national-Israeli. What remains of the Kookist package, then, is the veneration of nationalism, but without the translation of nationalism into a theological language.

There still are religious Zionists, of course, who believe in the coming of redemption and in the settlements as the central project that is hastening it. However, they have been marginalized and now find themselves in a situation similar to that which preceded the Six-Day War. There are also religious Zionists whose halakhic identity remains very powerful and overrides the nationalist aspect. They are what’s known as “Hardalim” (acronym for national-Haredi), a group that coalesced parallel to the general disintegration of Kookism. These groups continue to abide by different versions of Kookism, but they constitute a minority in the religious-Zionist movement. For most religious Zionists, modern nationalism and the observance of the precepts constitute two separate foci of identity, and the former is becoming increasingly paramount.

From the ruins of Gush Emunim, then, religious Zionism emerges less halakhic and more nationalist. This is religious Zionism without messianic fervor and with a diluted Jewish identity, one that draws primarily on the national aspect and puts forward a simple, ethnocentric Jewish perception.

The late Yeshayahu Leibowitz was wrong when he predicted that disappointment in the messianic vision would lead Gush Emunim’s adherents to convert to Christianity. But he knew well that exalting nationalism to the status of a religious principle meant its deification: namely, its idolatrous positioning as the center of the religion. “The ‘religious’ arguments for the annexation of the territories,” he wrote in April 1968, are no more than “an expression of the transformation of the Jewish religion into a camouflage for Israeli nationalism” (translation from a 1992 collection of essays by Leibowitz, edited by Eliezer Goldman). Nationalism is the core, religion is the cover. Today we see vividly the grotesque result of the process.

However, it would be a mistake to think that the current stage in the tangled and tense relations between Jewish religiosity and Jewish nationality is the final one. From the moment they were separated by the birth of modernity, each of these two elements has been attracted to its twin. The desire to bring the public space under its wing is deeply embedded in the religious system that underwent secularization, all the more so in the case of all-embracing monotheistic systems such as Judaism and Islam. Holiness is to religion as blood is to the human body. Another attempt at unification, like the consolidation of God with his Shekhinah, of religion and nationality, is only a matter of time. And time, as we know, is all that needs to be leaped over in order to arrive at the End of Days.

:

—

Published in Haaretz today.