Not long ago, I awoke to a sunny morning in a B&B in Daliyat al-Karmel. It was the beginning of a family vacation, and I had forgotten my tefillin. There was no shortage of tefillin around, since I was on vacation with my wife’s extended (and religiously observant) family, and I was quickly lent a replacement pair. However, when I picked up the tefillin, I found them to be very different to my own. The straps were a different width, the boxes were a different size, and so on. I tried to lay them, but I simply could not. I did not remember exactly how. A few days later, I prayed again with my own tefillin without any problem – because with mine I remembered how.

That is, it wasn’t precisely “me” who remembered, but rather my body. I, as a self-aware consciousness, was not involved at all. My body simply moved quickly between the chapters of prayer without any intervention on my behalf. Nor did I need to “retrieve from memory” the best way to go about it, or to imagine an internal flowchart detailing the steps of the ritual. Everything was simply done – and done well.

So where is my memory? Is it in my brain? If so, why did changing the tefillin disrupt it? The fact that activating my memory required me to use my hands and also grasp a certain object suggests that recalling a memory is more than an intra-brain search.

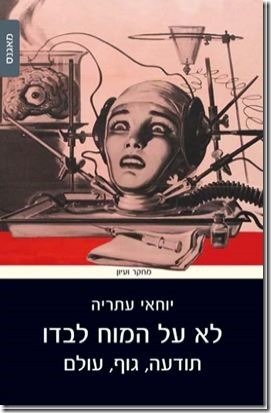

In his new book, Yochai Ataria makes precisely this claim. “Not by the Brain alone” (Hebrew) – the title of the book – is it that we are formed, Ataria claims. According to Ataria (a senior lecturer at Tel-Hai College and a scholar of the philosophy of mind and the philosophy of science), our subjective experience cannot be reduced the movement of neurons, i.e., to a particular form of activity in the brain. We are more than our brains, and to understand our subjective lives, meaning our internal lives and self-perception, our bodies and activity in the world must be examined.

In his new book, Yochai Ataria makes precisely this claim. “Not by the Brain alone” (Hebrew) – the title of the book – is it that we are formed, Ataria claims. According to Ataria (a senior lecturer at Tel-Hai College and a scholar of the philosophy of mind and the philosophy of science), our subjective experience cannot be reduced the movement of neurons, i.e., to a particular form of activity in the brain. We are more than our brains, and to understand our subjective lives, meaning our internal lives and self-perception, our bodies and activity in the world must be examined.

The World is not Projected Inside Us

Ataria challenges the view that has taken hold in the modern world, and which has also been adopted in the field of scientific inquiry, whereby a person is equivalent to their brain, so that if we were to understand every detail of the brain’s workings, we could also understand who and what a person is. According to Ataria, this view is rooted in error. A person’s sense of self and subjective experience are not located among the neurons within the brain, but rather in the system of interaction between a person – brain and body – and their environment.

Ataria begins with a critique of contemporary studies of the brain, and claims, together with experts whom he cites, that despite collecting an impressive array of data, research of the brain has not led to any significant theoretical breakthroughs. Impressive machines such as the fMRI can only reveal a certain increase in the blood flow to a certain area of the brain, often without allowing for any conclusions pertaining to the meaning of such occurrences. Citing the philosopher Michael Hagner, he claims that an apt analogy would be an attempt to evaluate the functioning of a computer according to the level of its power consumption as it executes various functions.

He continues by debunking the view that experiences or sensory perception are based on the brain processing data collected and inputted by the senses. The “representation” view, the little Cinema screen inside the head, the idea that the brain projects what it receives from the senses to an internal viewer who analyzes and acts on the information that reaches him or her (imagine the representation of internal life within the robot in the Terminator movies), is completely wrong and based on a dichotomous distinction between internal and external, i.e., on the assumption that our consciousness is located somewhere inside our head, and the world is located outside of it.

There is no such distinction, claims Ataria. Building on the philosophy of Husserl, Heidegger, and Merleau-Ponty, he describes consciousness as part of the world. When we assemble a puzzle, explains Ataria, we do not turn each piece around in our head, our spirit, or our mind, before placing it in its place; we try turning it with our hands in order to make it fit in the real world, until we position it correctly. Our consciousness is not in our head and does not act on representations. It is located in our hands and in the world surrounding us.

Similarly, explains Ataria,

I do not remember him [my son] abstractly, but rather in a certain way, at a certain event. I have no objective and detached representation, but always a memory from a certain point in time […] Memory is an activity that requires a basic level of physical activity. The body, I wish to make the case, is the backdrop for all our activity in the world – including the various cognitive activities.

Memory, like consciousness, is not detached from the world. It is not abstract, nor is it “representational.” It is connected with a specific time and place, to a body and to activity. It is, like our mind, grounded. The notion of a mind that is detached from the world, that represents the world to itself in a distant and dichotomous way, is theoretically misconceived and based on an illusion – an illusion that we live.

“The point of departure,” claims Ataria, “is not the thinking self but rather the acting self.” We are bodily beings in a physical world, not ethereal souls in a psychological world. As I once wrote,

We are beings that are situated within a body and can understand who we are and what the world is only by means of our body. This is the reason we use our hands when we speak, even on the phone. This is the reason we think better when we are walking. This is the reason our language is filled with metaphors of space and time whose purpose is understanding spirit and soul.

Indeed, we have no other (cognitive) way to understand the spirit and soul.

Ataria tries to support his claims by providing evidence across several chapters in which he cites interviews with people who experienced extreme situations vis-à-vis their consciousness: prisoners of war who underwent torture and isolation, and veteran vipassana meditators who experienced spiritual episodes of the Buddhist genre. Based on their testimonies, he develops a detailed, elaborate map of how human consciousness is developed by interacting with the world, emphasizing the emotional plane, rather than thoughts. (I will not provide in-depth descriptions here because the necessary background explanations are too extensive, but the discussion is fascinating.)

According to Ataria, there is no “flow of consciousness” that establishes our sense of self. There is no continuous consciousness at all, but rather flashes of mind. The internal sense of continuity, with which we are as familiar as we are with the palm of our hand, is based on the experience of our bodily encounter with the world. Without any interaction with the world (as Ataria concludes from POW and meditative experiences), our sense of self dissolves.

We are not Brains in a Vat

The notion of a “brain in a vat” – a well-known thought experiment in philosophy of mind describing a “Matrix”-like situation in which our brain is detached from the body and attached to wires that transmit information to it – is incorrect, at least if we think that such a brain would be capable of understanding itself or the world. The reality portrayed in the film, “the Matrix,” could not transpire. I explicitly asked Ataria to address this. Here is what he wrote in an informal email in response:

According to “the Matrix,” the notion of a “brain in a vat” is possible; in this way, for instance, Neo learns martial arts by “uploading” software to his brain. [However,] I do not think that our brain is a computer, nor do I think that all it does is execute functions (this, as noted, is the approach in “the Matrix” as well as in the cognitive sciences). In this sense, martial arts are not a [cognitive] function, they are a particular bodily activity that allow me to be present in a certain way in the world (I am absorbed into the world, which also contains me). This is a form of knowing how rather than knowing that. I am not saying (of course!) that the brain is not involved in learning processes, but not only the brain is involved. Moreover, I am not at all certain what people mean when they say that martial arts are a type of information.

But it does not end here. According to “the Matrix,” we understand that the brain is closed to the world, that we do not experience the world itself but rather a representation of the world (as brain researchers have told me more than once in the context of friendly conversation… “Do you really think that you see with your eyes?”). I maintain that even if there are representations, and to be more precise, even if we are capable of representing the world sometimes (I do not deny that we sometimes dream and imagine), ultimately the brain is open to the world – and I might even say that it is entirely open to the world, thus diffusing the border between the brain and the world.

Speaking of movies, what really comes across in the movie “Inside Out” is the idea that the “self” (not a sense of self, but a real Cartesian self) is located in the brain. Like some kind of central control unit. This is also the assumption underlying “The Matrix.” I do not think that there is a Cartesian self that is located in the brain. In fact, right now, while I am totally focused on this answer, I “forget myself” in favor of real-world activity.

“The Matrix,” in short, is just a movie, and there are no movies playing inside the head.

We will not Be Able to Upload Ourselves into The Cloud

These cinematic representations, in “the Matrix,” “the Terminator,” and many other science-fiction stories, suggest just how intuitive these depictions – of a brain inside a body, a “self” within a brain, an immaterial Cartesian consciousness, a homunculus (a “small man”) sitting inside our head watching events and controlling our body – have become, how accustomed we’ve grown to think of ourselves in this way, as beings that reside within the body, within the head, as a brain (or for those who believe, a soul).

The transhumanist fantasy that envisions “uploading” consciousness to a digital cloud or downloading one’s character as data that is saved on a hard disk belongs to the same mode of thought, as do all sorts of supposed points of “singularity” after which we will reside in digital space. Conversely, so do all kinds of horrifying predictions about artificial intelligence coming to life and controlling, from a station within a computerized control center, an army of robots sent to subjugate or destroy mankind.

These dreams and nightmares build on our Western point of view, but of course this is not the only way to perceive ourselves. This is one very particular way, which developed in the West as part of the Hellenistic culture, and from there was appropriated by Christianity. The sages of the Talmud, for instance, did not think that a person is a soul, but rather that he or she is primarily a body (powered, like with a battery, by a divine spirit given by God, and also taken away by Him, whereby a person, being the body, “returns his soul to the creator”). The Western-Christian mode of self-perception is taken for granted in the West, including also by Jews of course, but there is no reason to think that one cannot reach a different form of self-understanding.

What would a self-perception that sees the self as distributed across a broad interactive space, rather than something that is located within the brain, look like? I think that this is an extremely significant question. Would such a person be less egocentric? Would he or she be less self-centered – not as someone who possesses information, but as someone who lives an existential form of knowledge – in that he or she is not just a brain nor merely a body, but a body as well as everything that surrounds it? Would such a person be less anxious, at least inasmuch as anxiety stems from a limited and egocentric perception of our place within the world? Would such a person know how to traverse space more elegantly, like a dancer who moves spontaneously and naturally, rather than someone who tries to consciously control how they dance?

Even if we answer these questions in the affirmative, all of these wonderful advantages are overshadowed by the true accomplishment that a change to our self-perception entails: Ataria holds (and I think that he is right) that the notion whereby we are not merely a brain but rather a system that comprises consciousness, body and environment is also, ultimately, the truth. Meaning that altering our self-perception will allow us, supposedly, to live as we truly are. Imagine that.

—

Ataria’s book is impressive and fascinating. Nonetheless, I must say: it is not an easy read. It is replete with information, uses technical language, and aims somewhat higher than the average well-educated reader. Had I not possessed some background in Philosophy of Mind, it would have been even harder for me to follow and understand. At the same time, the investment is well worth it: Ataria achieves no less than a new way to understand who we are.

0 Responses to “You are not Your Brain – on Yochai Ataria’s new book”